Problems with the interpretation of Daniel 11

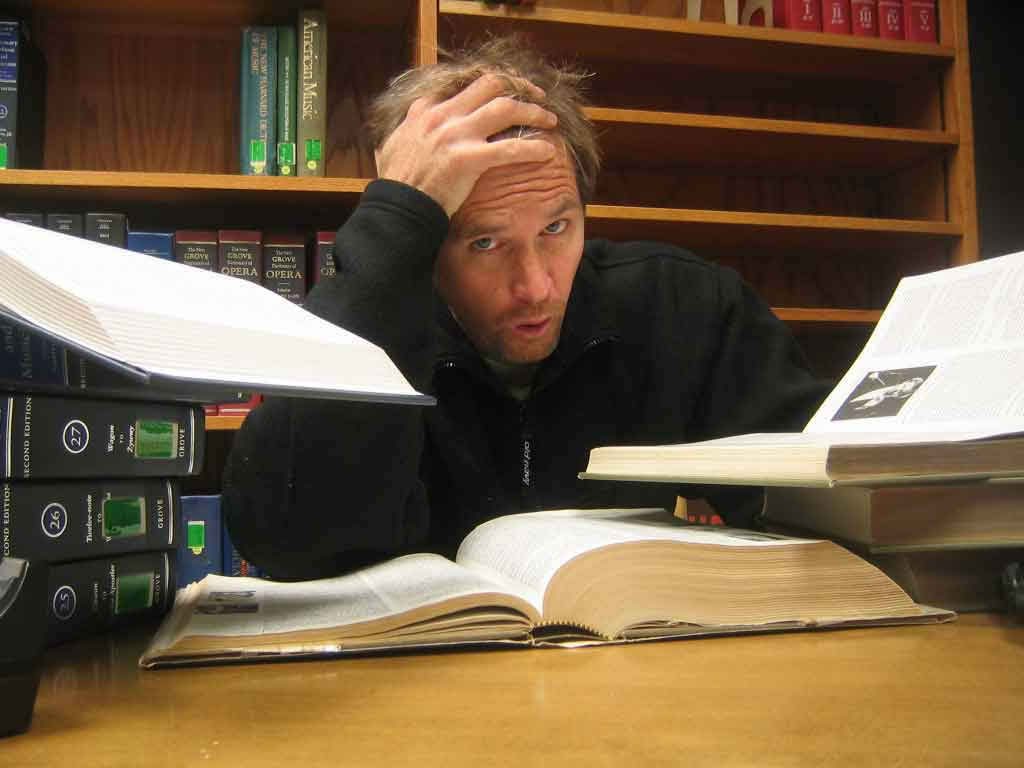

When reading the different interpretations of Daniel 11:5-45 from the following theologians, one can come to the conclusion that they find it hard to come to a common consensus, on which they all can agree on. Another problem amongst the following interpretations, is the use of Bible Commentaries and other means of interpretations before the use of exegesis. The study then becomes eisegesis, a reiteration of the common consensus of Bible commentaries, plus our own background knowledge and experience. But this is not exegesis.

What is exegesis?

The famous and time-honored Reformation principle repeated in modern times, namely that “Scripture is its own interpreter” or “the Bible is its own expositor,” derives fully from Scripture (for example, Luke 24:27, 1 Corinthians 2:13, 2 Peter 1:20). It means that “Scripture interprets Scripture,” that one portion of Scripture interprets another, becoming the key to other, less clear passages. This procedure involves the collection and study from all parts of the Bible of passages dealing with the same subject, so that each may aid in the interpretation of the other[1].

The question is, do we follow the basic steps of Biblical exegesis as outlined by Hassel or are we doing our own eisegesis and calling it exegesis. Examples of this anomaly used by the most respected theologians in our church are for example:

Uriah Smith

In his book “Daniel and the Revelation,” he describes the king of the North from Daniel 11:5-15 as the Seleucid dynasty ruling in Syria[2] and the king of the South as Egypt ruled by the Ptolemaic dynasty.[3] From verse 16-30 the Roman Empire became the king of the North and Egypt the king of the South.[4] From verse 31 to verse 39[5] the king of the North became Papal Rome. After verse 40 the king of the North becomes Turkey[6] and the King of the South is still geographically Egypt.

Mervyn Maxwell

He wrote a commentary on Daniel called “God Cares”. Maxwell divides the role of the Kings of the North and South with different rulers in history starting with the successors of Alexander the Great from the Grecian Empire. Daniel 11:5. The King of the North represents the Seleucid Kingdom ruling Syria lying to the north of Israel and the King of the South represents the Ptolemaic kingdom ruling Egypt lying to the south of Israel.[7] From verse 16 to 22 the king of the North becomes the Roman Empire and after verse 23 the title is transferred to the papacy whilst the king of the South represented the Muslims during the Crusades.[8]

Jaques B. Doukhan

In his book “The Vision of the End Daniel,” he describes the King of the North from Daniel 11:5-39 has having the same characteristics as the Little Horn in Daniel 7 and 8.[9] The King of the South represents man´s government without God which we would call atheism and an example of this would be Egypt from the Old Testament.[10]

Desmond Ford

In his book “Daniel,” he describes the King of the North as the enemies of Israel for example Syria, Babylon, Medo-Persian, Greece and much space is devoted to the Seleucid dynasty, especially Antiochus Epiphanies, whilst the king of the South represents the enemies of Israel to the south which was Egypt. Ford goes on further to explain that the King of the North in the new covenant times is spiritual Babylon and the king of the south is spiritual Egypt that denies Yaweh.[11]

William H. Shea

In his book “Daniel A Readers Guide,” he describes the king of the North as Syria including Babylon and the king of the South as Egypt. After the reign of Alexander the Great of Greece, the Seleucids took over the role as the king of the North and the Ptolemy’s took over the role as the king of the South as described from Daniel 11:5-14.[12] After Daniel 11:15 the role of the king of the North is transferred to the Roman Empire up to verse 22.[13] From verse 23 to verse 39 the king of the North becomes Papal Rome who battled with the Muslims and Egypt (the king of the South) during the Crusades.[14] From verse 40 to 45 the king of the North is still papal Rome and the king of the South would take on a spiritual phase like rationalism, atheism, communism, humanism and agnosticism.[15]

It is alright to have different meanings of a text in the Bible from different theologians; however these different meanings should be based on a sound exegetical study of the text and the rest of the Bible. This is not the case with the for mentioned theologians. One of the dangers of referring to theologians and commentaries before the use of exegesis is that the text becomes whitewashed with double meanings and then along with confusion to what the text is really saying.

Exegesis v Eisegesis

John J. Collins

An example of what I am saying can be taken from the commentary Hermeneia, in the book of Daniel, interpreted by John J. Collins[16]. Now I have never met Collins, but when I look at the first few pages of his book, this tells me that he is on the faculty of the theological department at Notre Dame University, which is a Roman Catholic university near South Bend, Indiana, USA. Upon reading some of his interpretations of chapters Daniel 2: Daniel 7: Daniel 8: and Daniel 11: I would say this guy is a genius at using modern methods and tools of interpretation. He is an expert in his field. His excellence in the study of the book of Daniel is second to none. This theologian knows what he is doing. However, he is not using exegesis but eisegesis.

What is the difference between exegesis and eisegesis?

The proper method of exegesis of God´s word entails word studies, not from Kittel´s Theological Dictionary or from Botterweck and Ringgren´s Theological dictionary. Why? Because these men are not perfect and they come to their word studies with presuppositions which all theologians do. However, your presuppositions may not agree with theirs; so it is best to do your own word studies of the whole Bible from Genesis to Revelation, and it is best to do your own syntax study of Bible passages, going back to the original Hebrew or Greek etc. This does not only mean studying the time period of the text but involves all time periods of the whole Bible. When all the ground work is done in your personal exegesis, then you can compare your findings with the study of other theologians on the subject, but not before.

Exegesis with Dr Norman Young and Dr Richard Davidson

In addition I would say it would be a great help to those who do exegesis, that when the study has been done, then get someone to examine it for you. One of the best exegetical duo studies I have seen is the one between Dr Norman Young, professor from Avondale college, Australia and Dr Richard Davidson professor at Andrews, Michigan, USA. This study was open to all on the internet. They were discussing which day Paul was talking about in Hebrews chapter nine. Was it the day of atonement, or the day of inauguration of the tabernacle? The way they criticized each others study, not in a negative way but to understand the text, was a marvel in itself; just to see how they learnt from each other, so as to come to a better understanding of the text. This is the ideal when doing exegesis: that is two theologians doing exegesis together.

The tendency today is to skip the long tedious study of word studies from the whole of the Bible and in depth exegesis, and quote some well-known theologian who has already studied the passage thoroughly. This method is wrong, but it is used in all protestant universities in the world, because it saves time. This kind of Bible study white washes the Bible doctrines and enables one theologian to have an authoritive meaning on a text and another theologian another meaning on the same text. These studies create double meanings of texts or even more, as in the case to my introduction and seeing the discrepancy of five theologians in the Adventist church over the explanation of Dan 11:5-45.

Eisegesis is imposing the theologians own interpretation into the text, without doing the real ground work of exegetical studies. In so doing, one white washes the doctrines of the church, with the use of quotations from theologians, commentaries, historical-critical method, source criticism, form criticism and redaction criticism. Some theologians take a text and only study it in that time setting, ignoring the rest of the Bible. Other theologians use other languages in that time setting, hence bringing double meanings to the text. All in all, different theologians who study the same text, come out with different conclusions and double meanings, bringing confusion to what God has stated in the text. This is called excellent scholarship in the area of theology and many protestant and Seventh-day Adventist theologians follow in the footsteps of these eisegesis theologians, looking to be recognized in the top theological circles of the world. However this is not exegesis dear friends, it is eisegesis, leading not to an understanding of God´s word, but to enhance oneself at the top of the theological ladder.

Method of study

I will attempt to do an exegetical study of Daniel 11: using the tools of proper exegesis and that includes word studies from the whole of the Bible, syntax and Hebrew grammar. Furthermore I will only use historical sources to fill in the time being explored by the text. The historical books I am using are: A History of the Christian Church by Williston Walker[17], this is a pro-protestant book. The other source is: A Lion Handbook: The History of Christianity,[18] and this is a pro-Roman Catholic book, hence giving a balanced historical information of the period being studied. I will not use footnotes for these historical sources, but just enter the authors surname and page number when quoting from them.

1. Introduction-The problem with Daniel 11:

2. The Little Horn power in the Hebrew text of Daniel 11:

3. Who is the king of the North in Daniel 11?

4. Who is the king of the South in Daniel 11?

5. Daniel 11:14

6. Daniel 11:15-20

7. Daniel 11:21-25

8. Daniel 11:26-29

9. Daniel 11:30

10. Daniel 11:31.32.

11. Daniel 11:33

12. Daniel 11:34

13. Daniel 11:35-39

14. Daniel 11:40

15. Daniel 11:41

16. Daniel 11:42.43.

17. Daniel 11:44.

18. Daniel 11:45

19. Daniel 12:1-3

20. Daniel 11: Conclusion and recommendation

[1] Gerhard F. Hassel, Biblical Interpretation Today (Washington D.C.: Biblical Research Institute, 1985), 102.103.

[2] Uriah Smith, Daniel and the Revelation (Washington D.C.: Review & Herald, 1944), 237.

[3] Ibid, 236.

[4] Ibid, 245,246.

[5] Ibid, 270.

[6] Ibid, 294.

[7] C. Mervyn Maxwell, God Cares, Vol. 1 (Nampa, Idaho: Pacific Press, 1981), 284.

[8] Ibid, 293- 294.

[9] Jacques B. Doukhan, The Vision Of The End Daniel (Berrien Springs, MI: Andrews University Press, 1987), 79.

[10] Ibid, 86.

[11] Desmond Ford, Daniel (Nashville, Tennessee: Southern Pub. Assoc., 1978), 254.

[12] William H. Shea, Daniel A Reader´s Guide (Nampa, Idaho: Pacific Press, 2005), 241.

[13] Ibid, 245.

[14] Ibid, 251.

[15] Ibid, 264-265.

[16] John J. Collins, Hermeneia: Daniel (Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 1993).

[17] Williston Walker, A History of the Christian Church (Edinburgh: T & T Clark, 1963).

[18] Tim Dowley, Ed., A Lion Handbook: The History of Christianity (Herts: Lion Publishing, 1977).

Copyright © 2014 by Tony Butenko

All rights reserved, including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form.